The Textbook

MRS. NELSON WAS obviously a total bitch.

To begin with, the moment the bell rang at 12:50 she would say, “To your seats, please.” If you whispered to the person next to you, she’d call you out by name, like, “No distractions please, Leda.” She assigned more reading than you could possibly do in one evening, especially considering that high school students had five other classes besides just History.

“This is advanced placement history,” Mrs. Nelson would say if the students complained about how fast she was lecturing. “If you can’t keep up, I’ll be happy to sign your transfer slip to another class.”

There was an exam every week, thirty multiple-choice questions that Leda could never remember the answers to—what was the population of the colonies in 1750, what year were the Townshend acts passed, what percentage of tax was enacted by the Sugar Act—plus a critical thinking question that was the only part she got full points for. The tests were photocopied with formatting that was the same as the layout of the textbook, curly banners and boxes that looked like little parchment scrolls. She got D’s on the first two exams, a C- on the third one.

For the fourth exam, she made a complicated study schedule with flashcards and notes and review sessions. She got a D+ on that one. After that she decided there was no point studying, just read the book and hope for the best.

Mrs. Nelson wore blue flowered dresses that spilled over her thick frame like bedsheets, hair done into a helmet like a fifties housewife.

“Notebooks out,” she would say, positioned behind her podium, stack of notes in front of her. Then she was off, lecturing so fast that you couldn’t write it all down unless you used shorthands: JT for Jamestown, SS for Southern slave-owners, FF for founding fathers.

Sometimes she’d stop lecturing without warning to ask questions. “Why did the colonists start the Revolutionary War?” Which hurt Leda’s brain, switching gears so quickly from writing to thinking. But the answers from kids in the class hurt her brain more.

“Liberty,” they would say. “Freedom from oppression.”

Which was fine if all you had read were the little side-boxes in the textbook, the ones called Words of Our Founders and Foremost Facts. All those supposedly inspiring quotes from Thomas Paine and Patrick Henry about conquering tyranny, the ones that were more like advertising slogans than actual historical knowledge.

What actually was the tyranny, Leda wondered? What was this extreme British cruelty that couldn’t be tolerated by the colonists?

It wasn’t, like, murder or anything. Mostly, in fact, it was one particular and much less cruel thing.

“Taxes,” Leda said.

Everyone laughed like it was a joke. Trevor Hagopian turned around and dropped his jaw at her to show he thought she was a dumb-ass. It made Leda’s heart race like she was about to fight, but she kept her face blank as much as she could.

“I’m serious,” she said. “Everything that pissed them off was basically taxes.”

That was one foremost fact Leda knew for sure. Even if she couldn’t remember the exact dates and percentage amounts of all those acts on the photocopied exams—the Stamp Act, the Sugar Act—she knew pretty much every single one of them was a tax.

“Angered them,” Mrs. Nelson corrected, looking down at her book. “What kind of people are angry about taxes?”

“Everyone,” Trevor said.

“Rich people,” Leda said.

Mrs. Nelson didn’t say anything, just started back up with her lecture.

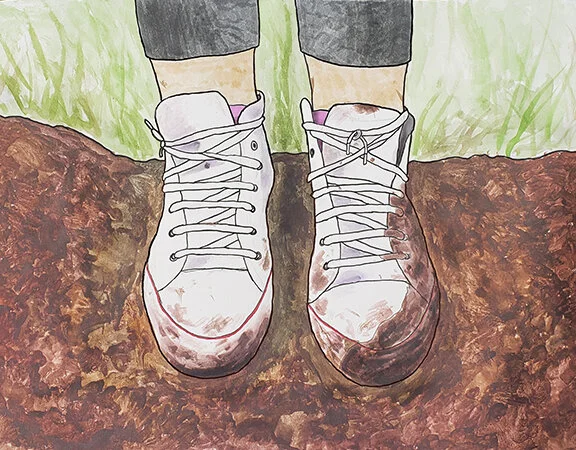

The first week of October it rained, a pounding, flooding rain that never usually came to California. Leda ran out to the lawn with her friends, danced in the puddles, mud soaking her sneakers and splashing up the shins of her jeans.

Then the first bell rang. Lunch was over.

Leda’s friends all decided to go home for the rest of the day, but there was a history test as usual coming up on Friday and Leda didn’t want to miss any information. She wrung her hair onto the lawn, shuffled her sneaker bottoms dry on the pavement, and walked into Mrs. Nelson’s class just in time for the second bell. She walked past everyone to her regular seat in the back and sat down, her wet jeans cold between the plastic seat and her skin.

Mrs. Nelson didn’t say anything, just started up her lecture like normal. Everything from the textbook chapter, in order: the personal history of Benjamin Franklin, factors leading up to the Treaty of Paris. Blah blah blah Yorktown blah blah blah Westward Expansion, Leda, please see me after class, then right back to lecturing like nothing had happened.

Half the class turned to look at Leda, including Trevor Hagopian who was eyeing her with exaggerated disgust like she was covered in trash instead of water. Leda kept writing, head bent low over her notebook, watching the ink smudge across the page from the wet sleeve of her sweatshirt.

When the bell rang at 1:50 and everyone got up to leave, Mrs. Nelson stood in front of her desk waiting for all the other students to leave. Leda walked to the front of the room, trying not to let her sneakers making squishing noises on the carpeted floor.

Mrs. Nelson looked her up and down, studying her. Leda hated when people did that, so she did it back: the blue flowers rippling over her bosom, the faint smell of onions wafting off her clothing like she’d been cooking recently. The thin lips twisted in a little scowl like she was trying to make a decision.

Then, decision made, Mrs. Nelson walked behind her desk and opened one of the drawers.

“I have something for you. Let me just find it.” She opened a second drawer, removed a messy stack of papers to look underneath. “Here it is.”

The book she handed to Leda was large and white and plain-looking. A People’s History of the United States.

“I want you to read this instead of the textbook. Read chapter four for next class.”

Leda flipped the book over. It was new, the spine unbroken. A quote on the back said, “a brilliant and moving history of the American people from the point of view of those whose plight has been largely omitted from most histories.”

“This is your copy,” Mrs. Nelson said. “You can write in it as much as you want. Keep bringing the regular textbook to class, but don’t bother reading it. This one is better.”

It seemed like some kind of trap, insulting the class textbook like maybe she was trying to trick Leda into agreeing.

“Why don’t you just switch books?”

“Textbooks are mandated by the district.” Mrs. Nelson started organizing the papers she had just pulled out of the desk drawer, dividing them into three small piles. “So, here’s what I need you to do.”

Leda opened the book and found chapter four. It seemed to be about how the leaders of the revolution wanted to distract poor people from the wealth inequality in the colonies. No side-boxes, no Words of our Founders or Foremost Facts. No Dates to Remember or Key Terms. Just an explanation of what happened and why.

It looked reasonably interesting.

“Every day, when I’m lecturing about the textbook,” Mrs. Nelson said, “I want you to raise your hand and ask questions based on what you learned in The People’s History.”

Leda looked up from the book to make sure she’d heard correctly.

“I’ll act annoyed when you do it.” Mrs. Nelson kept tidying the piles, securing them with paperclips, like this was all normal, no big deal. “But then we’ll discuss whatever you brought up. If you do a good job, I’ll give you an A in the class, even if you keep failing the exams.”

“Okay,” Leda said. “I can do that.”

“Obviously if you tell anyone about this, I’ll deny it.” She put the piles of paper back in the drawer, closed it with a decisive clicking noise. “All right, then, that’s all. You can go. Oh, and about playing in the rain before class.”

Leda froze, her hand halfway into her backpack as she put the book inside.

“That was a good idea,” Mrs. Nelson said.

If you like it, share it! www.ledalevine.com/textbook