The Dishes

MADDIE’S NAME WAS lighting up Leda’s phone for the tenth time this afternoon. The phone was on silent, to spare her nerves, but still it lit up with each missed call. And the texts were still coming through.

Hey, you around?

You know I’ve always got your back.

I’m your most loyal friend.

Your most loyal friend.

Why don’t you answer your phone.

Leda turned the phone over so she couldn’t see the screen.

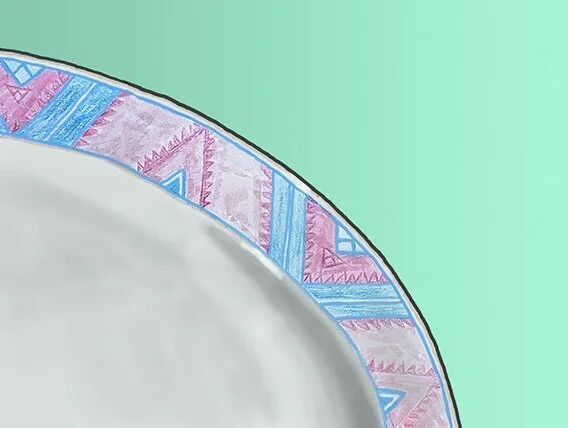

She went over to her small kitchen, washed three dishes out of the pile gathering in her sink. She couldn’t wash too many at once or the smell made her want to throw up. The dishes were a new set she’d bought for herself a month before the lockdown started. She loved the pattern around the edges, angles interlocking into diamonds, the subtle richness of fawn and seashell.

She’d had the dishes for a couple months, had given all her old, mismatched ones to Goodwill. It gave her a thrill to open the box and pull them out of their tissue, plate by plate, made her feel like a grown-up with an Instagram apartment. The kind of apartment you could invite someone over to and not feel like they were looking past your façade and right into all the grimy and unkempt parts of your soul.

Right after she bought the dishes, someone posted an article on Facebook about appropriation of Indigenous textile patterns. Leda became ashamed of her cups and plates and bowls. Now they were a sign of cultural imperialism and a type of cluelessness that most people would attribute to her white side, though she wasn’t sure her Asian side was so innocent of it. But certainly her mother would never buy dishes like these, so Coachellaish. Her mom would have picked a nice warm gray, no pattern, like something in Real Simple magazine. That was more her vibe, blankness, cream colors, which was why Leda had spent the years after the divorce in an apartment with no books except the ones she kept in her room, because books were cluttering to the visual field, her mother said. Maybe a rebellion against Leda’s father, the English professor, books on every surface: the kitchen table, the nightstand, the back of the toilet.

When Leda washed the dishes, ate off them, stacked them in her cabinet, she imagined that sad Indian from the television commercial. Her elementary school teacher had played it for the class during Native American Heritage month. Leda had wanted to be him, so stern and serious and in touch with nature, a single tear running down his cheek as white people threw garbage onto the beach.

Luckily there was coronavirus and no one was coming over to see her dishes, which was probably for the best because Leda still thought they were unspeakably beautiful even if she was deeply ashamed of them.

With the three dishes on the drying rack, she looked at her phone again. A missed call from Maddie. No new messages.

Leda looked out her kitchen window. She could see the freeway overpass a block away, but not the small, messy city of people who lived under it. A horrible place to be basically at any time, but especially during coronavirus, with no forty seconds of a warm-water faucet, no soap to dissolve the outer membrane of a virus. What happens to a baby, she wondered, picking up a bowl, then setting it back in the sink unwashed, throughout its life that determines whether it ends up living in a rent-controlled one-bedroom in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood or in a tent under the freeway?

She promised herself she’d leave some hand sanitizer for the people under the freeway, once she could get some. She had ordered two large containers of it that were supposedly coming from China in three weeks. Maybe she could leave them one. Maybe she could pick up some water jugs to leave as well, on her weekly masked trip to Trader Joe’s. Normally she didn’t buy stuff in plastic, but this was a pandemic.

She checked the phone again. Another message from Maddie. She was getting more to the point now.

Just fifty dollars, the message said. Paypal is fine.

It was about to get ugly from here; it always did. Best to turn the phone off altogether, but she was waiting for a text from Matt. She’d texted him two days ago, a text that said, “I really need to talk to you.”

So far, no response.

In a technical sense, he didn’t owe her one. After seven months of dating, he had broken up with her a month ago when lockdown started. His hypochondria, which was pretty ridiculous under normal circumstances, was through the roof.

“I just don’t think I can see anyone during all this,” he said on the phone. “I mean, it’s not really safe, is it?”

“What’s not safe?” Leda asked.

“You know.”

She remembered that time he found a lump in his testicle and he wouldn’t have sex with her or even let her stay over while he was waiting for the biopsy results to come back. All he wanted to do was sit around moping in his cold, dark bedroom by himself.

He would be a horrible father, Leda thought.

She was pretty sure you had to be resilient to be a parent. Couldn’t be melting down all the time, nervous about every little thing, or the big things. Even if you did everything right, it could all go wrong. You could raise your kid in the town with the best schools, buy her everything she needed, make sure her friends were the right sort of people, in honors classes and headed for good colleges, but it didn’t matter; she could still run away to New York and fall in with some sketchy people and end up with an opioid addiction that turned her from a shooting star to a bitter, hateful husk, an empty vessel spitting at formerly-loved ones, I need, I need. You couldn’t go around fretting about it, worrying your child would end up cycling in and out of rehab facilities and no-income living facilities and the couches of people she used to date and sometimes no one knew where.

Even when they were together, Matt never wanted to come to Leda’s apartment, which was filled with old books from college and stuffed animals from her childhood bedroom and various small vases and antique bottles mostly from Maddie, who used to give them to her for birthdays and Hanukah and sometimes for no particular reason except she saw one she thought Leda would like. Matt was one of those software engineers who didn’t get attached to things and so everything in his apartment was minimal and new. His kitchen counters didn’t have anything on them except the instant pot that he cooked basically all his food in and a really fancy espresso maker plated with sparkling chrome. No knickknacks, just a single bookshelf with maybe ten books on it and a basket full of remote controls for his giant TV. Leda didn’t even have a TV, just an IPad that she watched movies on, which was another reason Matt never wanted to come over.

If she was honest about it, she’d bought the new dish set to make her apartment feel like a grown-up apartment, so she wouldn’t feel so embarrassed when he came over. He’d only eaten off of them one time, right after she’d bought them, when she forced him to come over and have dinner. She’d made a lasagna that turned out decent, had wine in a new set of glasses, but even still he ended up going back to his place after dinner, letting her know she was welcome to join him, which she did.

Leda’s stomach was gurgling, like it had been doing all the time lately, a disconcerting tug in her belly that felt somewhere been hunger and indigestion. She took a clean bowl off the dishrack, put in some yogurt and granola and honey. What she really wanted was bread with peanut butter and banana slices, her favorite snack, but none of things were ever at Trader Joe’s anymore. Leda hadn’t seen a loaf of bread on a shelf since February. But they did still have some large tubs of yogurt, which was easy to eat and nice to look at, the creamy white offset by the golden honey, the pink pattern along the rim of the bowl.

Leda lay down on the couch and placed the bowl on her chest. This was how she’d been eating all her meals for the last month. She was too tired to sit up, especially when she ate. Everything smelled weird to her, a lingering dishwater smell that turned her stomach, and it took a lot of energy not to throw up.

She should probably pack all those little bottles from Maddie away, she thought as she ate. They were dust magnets and easy to brake, not a good item for a grown-up apartment, which was what she needed her apartment to be now.

She checked her phone. No message from Matt. One more from Maddie.

Will you be happy when I can’t afford to eat this week, Maddie wrote. If I starve all week will you be happy then?

Leda took a bite of yogurt, crunched the granola between her back teeth. It wasn’t so bad if she let it soften slowly in her mouth before swallowing.

After a few bites, she decided she didn’t need Matt’s permission to keep the baby.

She opened up the contacts in her phone, found Matt’s number and pressed “block.” Then she blocked Maddie’s number, too.

Matt never said anything about it but Maddie did, in a series of threatening messages on Leda’s mom’s voicemail. But she was in New York and didn’t have enough money to buy her next bottle of pills or bail out her boyfriend or whatever it was she was after, much less fly to California, so Leda wasn’t too worried.

If you like it, share it! ledalevine.com/the-dishes